Does squishy, boot-sucking mud give you the willies? Are you terrified of snakes and leeches and poison sumac? Do you fear that a ghoulish, slime-covered hag will pull you under the water and drown you? Most of us probably don’t worry about the latter, but tales of malevolent beings or spirits in wet and mucky places are found the world over.

These stories sound fanciful to modern ears but have roots in real-life concerns of our peasant ancestors, few of whom could swim even though their villages were often located near water. Tales of spirits and demons probably helped instill an appropriate caution about wetlands in both children and adults. Surely many a peasant girl warned of the Rusalki when her fiancé headed to the tavern, lest he stumbles tipsily into the town pond on his way home.

British folklore warns that passing by a marsh on a misty evening means risking an encounter with Jenny Greenteeth, a sharp-toothed crone who pulls unwary wanderers into the depths and devours them. Even today in parts of England, “Jenny Greenteeth” is another name for the duckweeds (Lemna sp.), aquatic plants whose tiny leaves form a continuous mat over the water’s surface that may appear as solid ground to the eyes of the very young or very old.

Finnish children must beware of the Näkki — a shape-shifting water spirit that grabs at little ones who lean a little too far over the dock or the edge of a pond while gazing at their reflection.

Rusalki are the ghosts of drowned Russian maidens who entice bachelors with their singing and dancing, then drown them or tickle them to death.

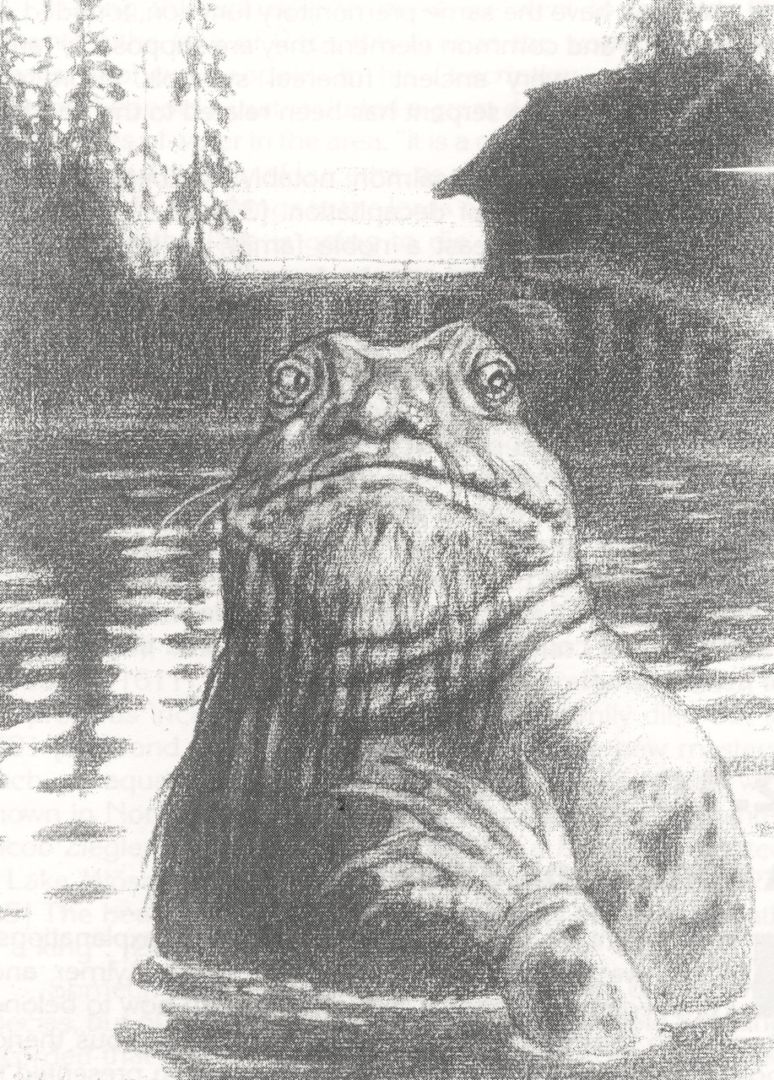

The Vodyanoy of Slavic Europe resembles tiny old men with algae-covered hair and beards (some accounts give them frog-like features). When not loafing on sunken logs and smoking their pipes, they drown human invaders of their watery territories and keep their souls in porcelain cups. But fishermen who place a pinch of tobacco in the water and call out “Here’s your tobacco, Lord Vodyanoy,” may find themselves rewarded with a large catch.

Some descriptions of the Kelpie – the Celtic water horse who carries its hapless riders beneath the water to their doom – give it a mane of dripping bulrushes.

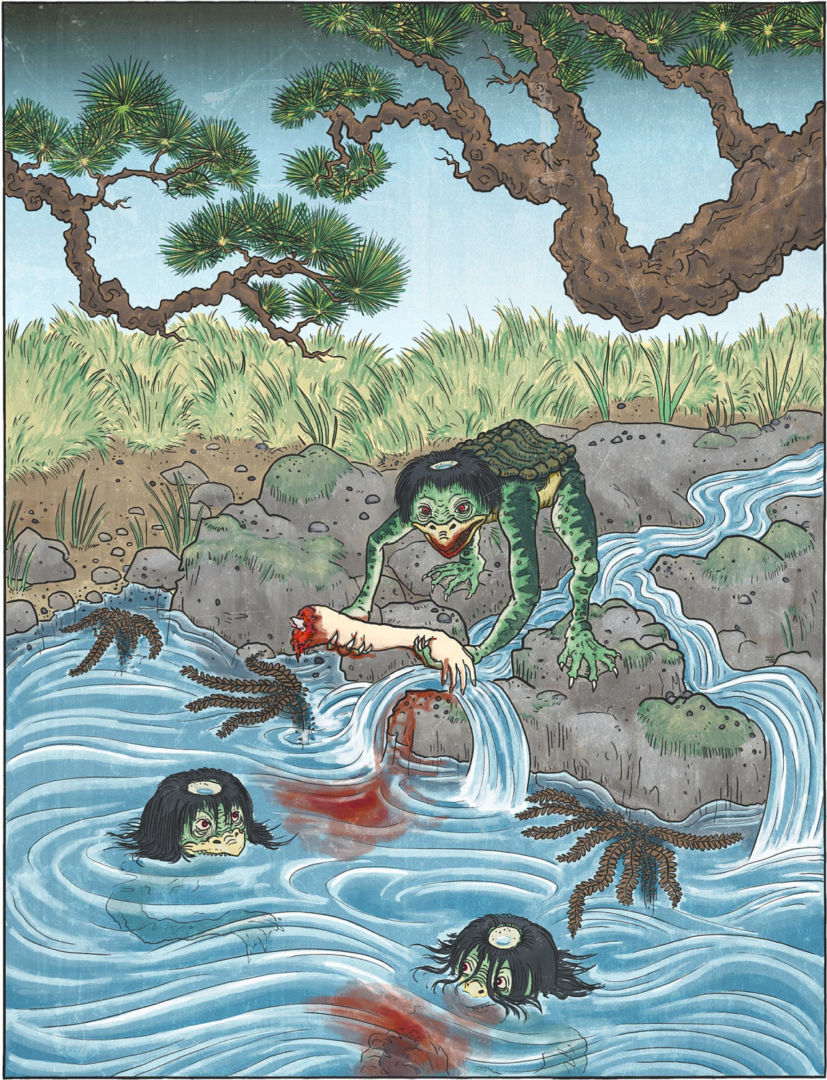

The Kappa of Japan is usually depicted as a kind of humanoid turtle with a carapace and webbed feet, though some insist it is based on the endangered Japanese giant salamander. The Kappa is a mischievous trickster whose behavior runs the gamut from loud farting and peering up women’s kimonos to kidnapping, drowning and eating people. The only thing Kappas enjoy more than a tasty child is cucumbers, so some Japanese parents would inscribe their child’s names on a cucumber and throw it in a pond or stream as an offering to ensure safe swimming.

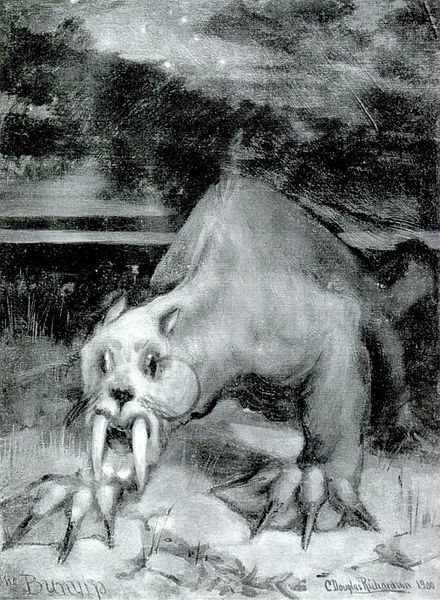

In the swamps and billabongs of Australia lurks the Bunyip, a beast of Aboriginal mythology that acts as a kind of wetland guardian. An ancient tale tells of two brothers who were turned into Black Swans and their village flooded after they captured a Bunyip calf. Descriptions lead scientists to believe the legend may stem from Aboriginal encounters with the bones of large, now-extinct wetland marsupials or perhaps the carcass of an elephant seal that wandered far inland and died on a riverbank.

A much kinder wetland guardian is Heqet, the frog-headed Egyptian fertility goddess of agriculture and childbirth. Heqet reigns over the annual flooding of the Nile (and, presumably, the seasonal emergence of frogs), whose nutrient-rich waters replenish the depleted soils of Egypt’s farms.

At least one tale traces directly to wetland management gone awry. Stories of the Tiddy Mun – a little old marsh man with shrill laughter like the pewit call of the Northern Lapwing, a wetland shorebird – date to the 1650s and flood control efforts in the coastal fens of Lincolnshire, England. When the drained peatlands dried and shrank, land levels dropped and flooding worsened. Enraged at the disturbance to his home, the Tiddy Mun issued a curse of pestilence on the villages involved. He was not completely without pity, however – when flooding threatened, townsfolk would chant his name until they heard the pewit call, whereupon the waters would miraculously recede.

Adapted from “A World of Wetland Monsters” by Tod Highsmith, which originally appeared in Wisconsin Wetlands Association’s 2013, Volume 3 newsletter.

Photos courtesy Wikimedia Commons, pumpkinrot.com, and Keith Hoberg.

Related content

Hallowed shallows: Moving beyond the haunted history of wetlands

From the Director: What brings us together

Reflect on what brings Wisconsin Wetlands Association together: our love for wetlands.