This is the fourth and final in a series of four blog posts on hydrologic restoration in Wisconsin. Read part 1, “How wetlands manage water,” part 2, “Changes to our land, challenges to our water,” and part 3, “Our legacy of wetland loss: Behind our water problems.”

We’ve seen how human actions have disrupted hydrology and brought widespread societal and ecological challenges. Now, let’s look at how we can reverse (and are reversing) the damage.

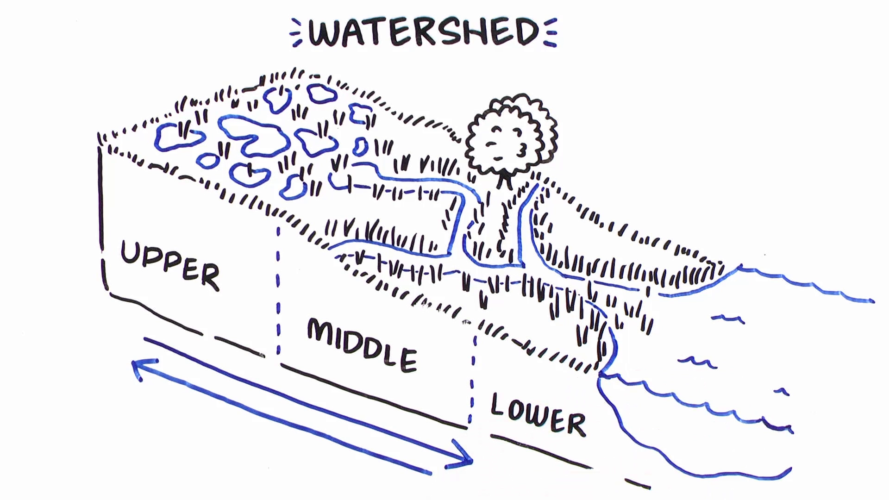

Let’s start by examining the common elements of successful watershed-based hydrologic restoration.

Define the issues and set goals.

Effective watershed-based hydrologic restoration must begin with a shared understanding of the problem(s) the community wants fixed. Are roads washing out after rain events? Are algae blooms plaguing local lakes? Have local fisheries declined? Local leadership and community engagement are essential to gaining support and building momentum.

Address the root causes.

Too often, we spend time, money, and energy to “fix” site-specific problems while ignoring the root causes. Stabilizing an eroding riverbank addresses a symptom. Working upstream to increase storage and infiltration addresses the underlying conditions that caused the erosion and reduces the chance of needing to repeat our repair efforts time after time. Successful watershed-based hydrologic restoration addresses the sources of our problems, not just the symptoms. It uses an understanding of past conditions to inform the development of present solutions. This approach involves asking three key questions:

- How did water move across and through the landscape historically, and what natural processes/ features influenced this movement?

- What’s changed that has affected the movement of water?

- How can we bring back a semblance of historic hydrologic conditions in a modern context?

Take an interdisciplinary approach.

To answer these three key questions, we must involve many perspectives and areas of expertise. Geomorphologists and geologists describe what formed the landscape and how water moves. Historians and archaeologists explain how human actions have brought change over time. Hydrologists, soil scientists, botanists, and fish and wildlife biologists piece together what would be possible if the conditions were healthier. Engineers design restoration plans, quantify benefits, and install practices. Each perspective contributes to the whole picture.

Develop partnerships.

Because human landscapes can be as diverse as natural landscapes, solutions must fit within watershed and societal contexts; community involvement is essential. Agricultural experts, urban designers, cultural resource specialists, and planners help describe current human uses. Community leaders, agency staff, and policy-makers guide and help fund landscape-scale action. Private landowners are critical because neighbors working with neighbors is the only way to achieve lasting solutions.

What are some common actions involved in this work?

Much of the work in watershed-based hydrologic restoration aims to return natural water management characteristics to the landscape—or, when that’s not possible, to mimic them as best we can. The simplest solutions often prove to be the most effective. In most situations, upper watershed and floodplain areas are where work of this kind is most needed.

Restoring upper watershed wetlands.

Actions to slow the flow and increase infiltration will have greater value when implemented higher in the watershed—the higher, the better. Look for opportunities to capture runoff in small wetlands, strategically restore permanent cover like deep-rooted prairie grasses, or adjust tile and drainage infrastructure to slow spring runoff. In damaged areas, you might need to stabilize gullies and address land-use practices that contribute to flashy runoff conditions. Most important: use good practices (even if small or simple) in many places where they are needed to see results.

Reconnecting floodplains.

To restore floodplain function, we must allow the land to flood. Because so much human development has taken place in historic floodplains, we have to exercise care regarding where and how we direct floodwaters in floodplains. Fortunately, most watersheds do have areas where water can safely spread out. To reconnect floodplains, you may need to remove levees, stabilize river or creek grade, “re-meander” straightened channels, and/or remove accumulated sediment. Again, good, simple practices in many locations can deliver results.

What’s happening in Wisconsin?

Policies and programs implementing watershed-based hydrologic restoration are further advanced elsewhere in the nation than they are here in Wisconsin. That said, Wisconsin does have some great examples and we see increasing interest in and enthusiasm for applying watershed-based approaches.

We have a lot of work to do, but thanks to your support, momentum for this work is growing.

About photo at top: Tony Kuchma, Oneida Nation Wetlands Program Coordinator, points to wetland restoration work done by the Nation near Green Bay. Here, large-scale watershed restoration is driven by the need to restore cultural and natural resources for traditional use and to meet the community’s economic and housing needs. Photo by Katie Beilfuss.

Related content

Developing a shared understanding of watershed-based hydrologic restoration

How wetlands manage water

Take a look at how wetlands work together in a watershed to manage water.

Changes to our land, challenges for our waters

Our legacy of wetland loss: Behind our water problems