By Madeline Cleveland, avocational ichthyologist

If you look into the clear vegetated waters of a floodplain lake or river backwater on a sunny day in Southeastern Wisconsin, when the light is just right, you might be lucky enough to spot a constellation of tiny golden stars near the surface of the water. These little reflective “stars” are the distinctive markings that belong to Fundulus dispar, the starhead topminnow.

While fitting one common definition of “minnow” (a small non-game fish), the starhead topminnow is actually not a true minnow in a scientific sense. It is a species of killifish of the family Fundulidae. (True minnows belong to the taxonomic order Cypriniformes, while topminnows belong to the taxonomic order Cyprinodontiformes, the tooth carps.)

Although Fundulus dispar ranges throughout the central United States and is considered “Apparently Secure” on a national level, It is at risk of extirpation in Wisconsin due to pollution-related habitat loss and resource management oversights.

Starhead topminnows reside in the upper water column, usually swimming in small schools, rarely venturing below a foot of water (hence the common name) and almost always very near shore.

They prefer a soft substrate that groundwater be present in their habitat, and that the habitat have lots of submerged vegetation for shelter and in which to lay their eggs.

Their unique supraterminal (upturned) mouth allows them to skim the water’s surface in search of invertebrates, daphnia, and insects that have fallen in. Their diet also includes algae as well as some plant matter.

Living almost directly beneath the surface would seem to make the starhead topminnow highly vulnerable to predation, especially considering the obvious high-visibility star atop the head that seems to demand attention. It is thought that the stars are a form of biocrypsis, mimicking sunlight on the water, and are a way of hiding quite literally in plain sight, confusing predators from above.

And the topminnows’ survival strategy doesn’t stop at a showy scale atop the head. When pursued from below by one of numerous aquatic predators that share their habitat, such as bass or pickerel, the topminnow can leap out of the water to the safety of the shore to return once the danger has passed. Starhead topminnows are capable of terrestrial locomotion, and one study (Goodyear 1970) concluded that this species uses the sun to align its body toward or away from the water. Cool, right?

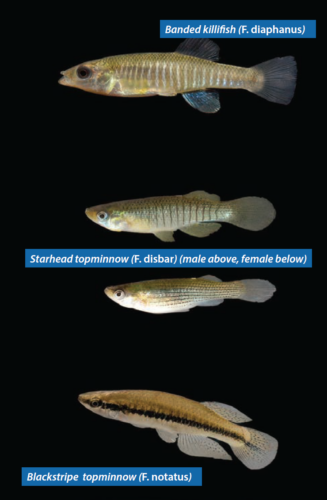

The Latin species name dispar means “different” and refers to the species dimorphism (males and females can be differentiated on sight). Females of the species have six to eight thin, dark, horizontal stripes on each side. Males have three to 13 dark, vertical bars on each side, and their fins are larger. In both sexes in most specimens, a black wedge-shaped marking extends downward from each eye. Luckily, if you happen to find a starhead topminnow in Wisconsin, you’ll have no trouble differentiating between it and any other fish in the state, including the two other Fundulus species that live in Wisconsin: the blackstripe topminnow (F. notatus) and the banded killifish (F. diaphanus).

The starhead topminnow is an indicator species, meaning that the health of their populations can tell us a lot about the health of our water and aquatic ecosystems. To conserve the starhead topminnow and its habitat is to conserve pristine backwater sloughs, oxbows, glacial and floodplain lakes, groundwater, and native vegetation.

The strongest, healthiest populations of starhead topminnows in the state can be found in the backwaters of the Lower Wisconsin River. And it was there that I encountered the starhead topminnow for the first time… outside of a book. It was a warm summer day, and we were under the shade of bird-filled trees. We’d and we’d just canoed a gorgeous slough where water lilies floated on calm, tannin-filled water near a beaver’s dam. Once ashore, I began to hear an occasional quiet splashing sound behind me. Upon closer inspection, to my surprise and delight, the sound was that of a small school of starhead topminnow enthusiastically feeding on mosquito larvae, which, if you’ve spent time near Wisconsin’s buggy summer waterways, will surely make you fall in love with the topminnows.

Norton Slough, near Spring Green along the Lower Wisconsin River. Top: 2008, before nutrient polluted groundwater, with diverse aquatic vegetation and a healthy population of starhead topminnow. Bottom: 2011, after nutrient-polluted groundwater, covered with duckweed and filamentous algae with very few starhead topminnows. Photos by Dave Marshall.

Unfortunately, multiple sloughs along the Wisconsin River, much like the one I visited, have been particularly negatively affected by polluted groundwater carrying fertilizer from nearby agricultural fields. This groundwater pollution causes a buildup of excess nutrients in the water, which in turn causes algal blooms and duckweed overpopulation. This overgrowth can block out light, killing many submerged macrophytes. The subsequent decay of plant matter and algae uses up dissolved oxygen and can cause the water to become hypoxic, virtually extinguishing all other life in the slough. If polluted, the groundwater vital to starhead topminnows is the very same thing that can destroy them.

Fortunately, a recent conservation project that aimed to restore starhead topminnows to some of their former range, has been a success. In 2018, 119 individuals were collected at seven different, carefully selected sites on the Lower Wisconsin River to be bred in captivity. And after three year’s work, 6,309 topminnows had been released into the wild. To this day, three reintroduced populations have been established.

The fate of this tiny, overlooked gem and its habitat hang in the balance. It’s an example of the kind of unintentional loss that can happen as we alter the landscape. However, without effective changes on a larger scale, the future could be bleak. Employing agricultural practices that require less chemical application (like regenerative agriculture and permaculture) as compared to conventional methods could be a very effective method of preventing water pollution and saving our sloughs.

To conclude, dear reader, when you see little constellations on the surface of the water, take a moment to stop and admire the humble starhead topminnow in its native habitat. There is much beauty and complexity to be found in such small things.

Related content

Wetland Coffee Break: Starhead Topminnow: The rare star of the backwaters of the Lower Wisconsin Riverway

Wetland Coffee Break: The fascinating fishes of the floodplains of Wisconsin’s largest rivers

Wetland Coffee Break: Wisconsin’s amazing native mussels