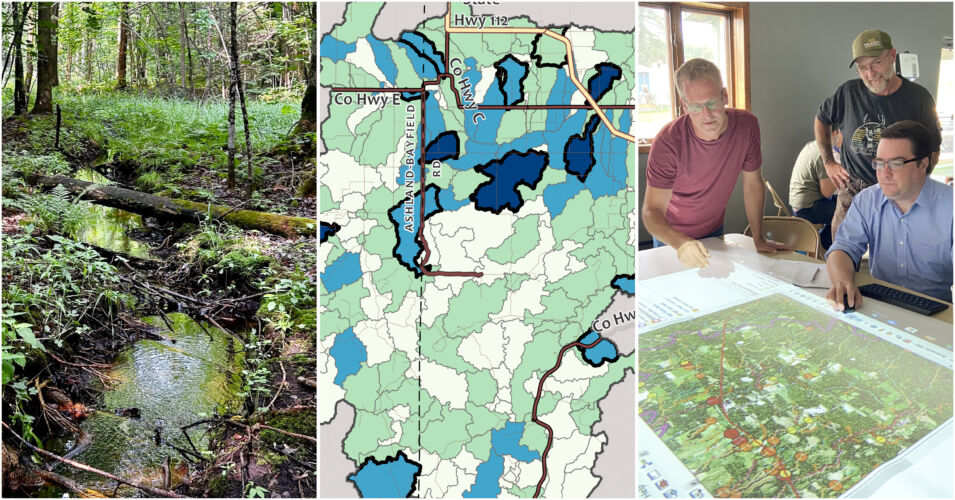

Since an extreme flood in 2016 drew our attention to the Lake Superior Basin, Wisconsin Wetlands Association (WWA) has been working to help communities in northern Wisconsin better understand how the loss of headwater wetland storage and floodplain connectivity contributes to flood risks and damages. These communities have been hit hard with catastrophic and repetitive storm-related damages to roads and culverts in recent years, with six federal disaster declarations between 2012 and 2022. These communities urgently need solutions to reduce flood risks and damages.

WWA is striving to meet that need by providing technical support to help assess the root causes of these flood vulnerabilities. We’re also working to build local capacity to prioritize, plan, and implement projects that combine wetland, stream, and floodplain restoration with bridge and culvert improvements to increase the resilience of vulnerable downstream transportation infrastructure.

Organized under the moniker of natural flood management this work has been carried out largely through a two-phased pilot project in the Marengo River watershed (Ashland/Bayfield counties).

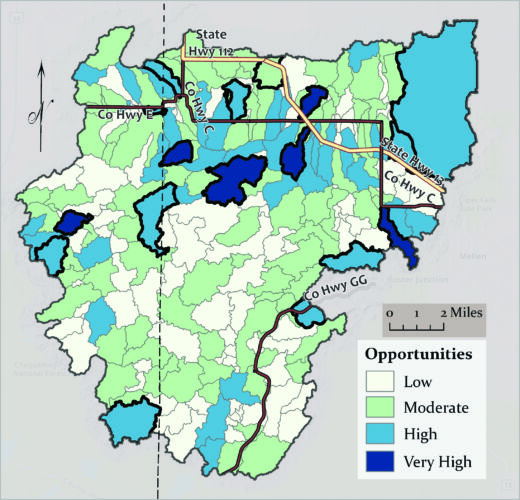

This map of the Marengo River watershed helps decision makers target their efforts by showing them which areas offer the most opportunity to restore wetlands—the darker the color, the greater the opportunity.

In Phase 1 (2019-2022), WWA helped Ashland County secure a Federal Emergency Management Agency Pre-Disaster Hazard Mitigation Grant. Through this project, the county hired WWA, the US Geological Survey, and the Northwest Regional Planning Commission to assess culvert risks and to identify and map fluvial erosion hazards such as ravines, gullies, and incised streams.

In Phase 2 (2021-2023), WWA and the Association of State Floodplain Managers received support from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative to further identify areas of compromised wetland storage, identify and prioritize hydrologic restoration opportunities, and begin scoping potential projects.

As we wrap up Phase 2, we’re reflecting on what we’ve achieved and exporting lessons learned to other key audiences. The following are some of the key outputs and outcomes from this important work.

Increased baseline data

Existing wetland inventories and other nationally available data underrepresented the extent of the wetland and stream network, particularly in headwater areas. Reliable information on culvert locations and damage histories has not been well compiled. The Marengo River watershed work has significantly increased the availability and accuracy of these and other key data sets needed to help flood-prone communities understand the root causes of flood risks and damages.

New assessment methods and decision-support tools

One project priority was to develop and test methods to evaluate culvert washout risks and identify where degraded wetland and stream hydrology contributes to those risks. We’ve also worked with partners to summarize and post underlying data and assessment findings so that local road managers can explore the data directly. These tools have helped build understanding of landscape conditions and restoration opportunities. They also provide an easy way for local partners to identify and begin scoping priority restoration projects.

Identification of new policy priorities

The purpose of pilot projects like this is to try new things and learn. The lessons learned from the Marengo River watershed projects have informed— and will continue to inform—WWA’s work to increase policy and program support for hydrologic assessment and restoration. For example, several of the provisions in the newly enacted Pre-Disaster Flood Resilience Grant Program are designed to help address capacity constraints and knowledge gaps we first observed in our interactions with Marengo River watershed collaborators.

Momentum for the use of natural flood management solutions

Through community engagement, partnership development, and local outreach, we have built a shared vision for the use of natural flood management across the Lake Superior Basin. The project has also garnered statewide and even national attention. This increased awareness and engagement is beginning to translate into increased public investments in hydrologic restoration as a climate adaptation strategy and the development of new constituencies for wetlands conservation. It has also opened the doors for new flood resilience collaborations with other Wisconsin communities and additional agencies. We anticipate being able to announce the details of some of these initiatives later this year.

For more information about the MRW pilot project methods and findings and to explore newly generated data visit the Marengo Watershed Strategic Floodplain and Wetland Restoration project website.

Related content

Illustrating hydrology and water management in a new StoryMap

What are floodplains? Managing misconceptions about healthy flooding