by Peter David, Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission

While wetlands are well known for their diversity and productivity, not many wetland lovers in the state head out to the marsh with the intent of gathering one of the most nutritious and delicious foods the region has to offer: the seeds of Zizania palustris, or northern wild rice.

Wild rice can be found in many parts of the state. Recent efforts to inventory northern Wisconsin beds pinned down more than 300 locations; the southern distribution is not as well documented. (Southern Wisconsin also has beds of the closely related, but smaller-seeded and generally unharvested, southern wild rice.) Rice grows in about 0.5-3 feet of gently-flowing water, usually in soft organic substrates. An annual plant in the grass family, it goes through submergent, floating leaf, and emergent stages of growth each year.

Manoomin, as is it known to the Ojibwe, played a significant role in the history of Wisconsin. The Menominee take their name from this plant, and many intertribal battles were fought over the control of good beds. The lines demarking Indian Reservations on the state map today often reflect the historical distribution of this plant, even though some beds, like those on the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation, were lost as settlers altered the landscape through dam and dredge.

Yet while the landscape has changed, the practice of ricing persists in a manner quite similar to the method used prior to European contact. The birch bark canoe has been updated, but the rest of the limited equipment remains largely the same: a pair of light-weight, wooden ricing sticks, and a long (perhaps 17 foot) push-pole.

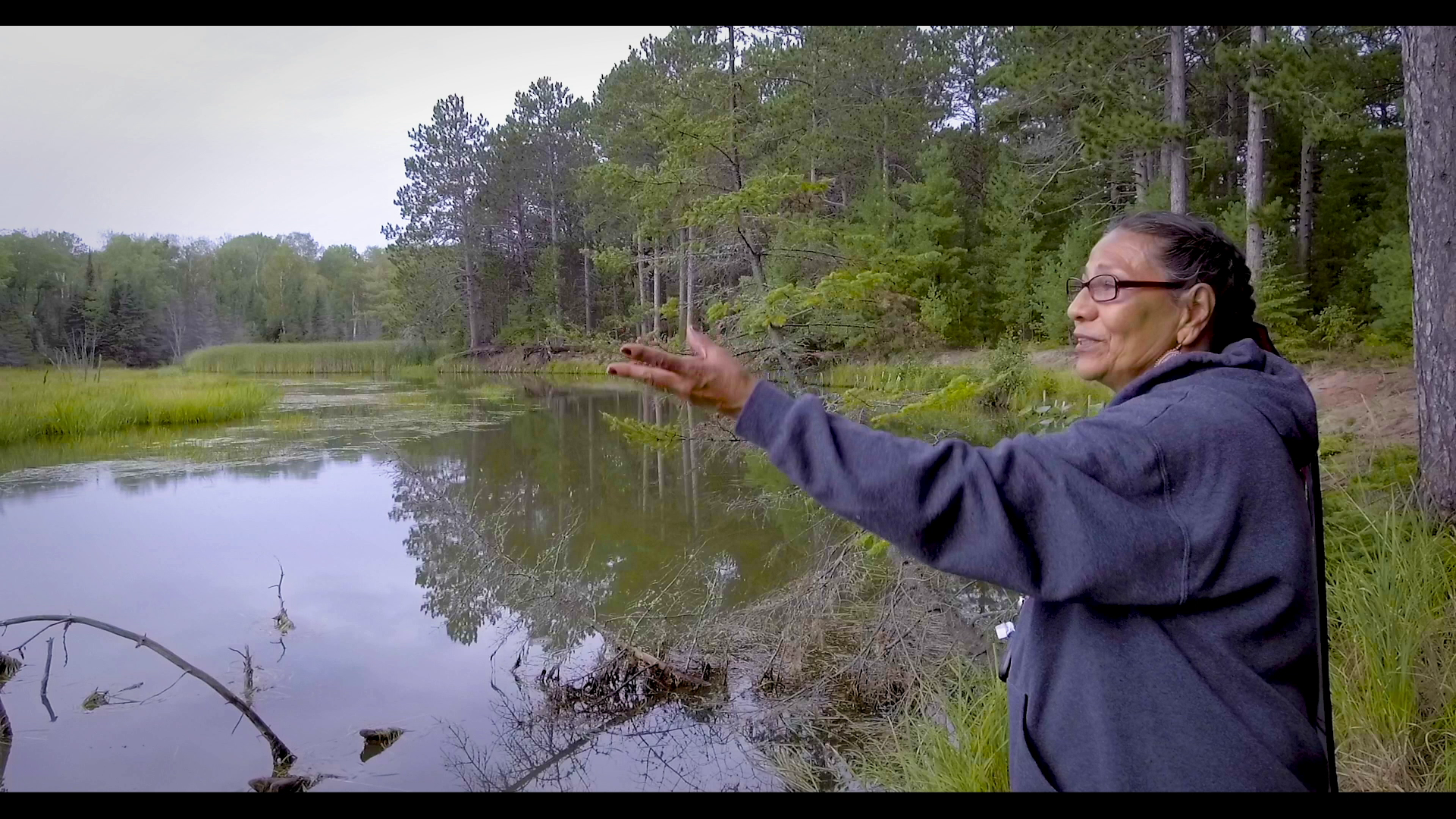

The surface of this Douglas County flowage is nearly hidden by the rice bed, but recent canoe passes from the first harvesting help delineate the manoomin.

The harvest season runs about 3-4 weeks, beginning in late August. Ricers traditionally work in pairs, with the poler slowly moving the canoe through the rice beds. The knocker uses one of the wooden sticks to lean the seed heads, commonly 2-4 feet above the water, over the side of the canoe, and the other to gently dislodge the ripe seed. Care must be used, because rice ripens gradually, allowing the same bed to be picked repeatedly in the same season if the plants are not damaged. A good team works together, developing a rhythm as they make parallel passes through the rice. An average trip will bring in 35-40 pounds of rice, but more than 100 pounds is possible.

Picking is only half the process of obtaining rice, however. Before it can be eaten, “green” rice needs to be finished. Finishing involves drying and parching the rice (which lowers the water content and allows preservation) and removing the sheath that envelopes the seed. Most contemporary ricers bring their rice to professional finishers. A typical finishing yield is about 35-40% of the green weight.

While putting manoomin on your table clearly requires some effort, the reward is great. There is nothing on the planet quite like wild, hand-harvested manoomin. Most say its flavor is markedly distinct even from the cultivated varieties of wild rice commonly found on the grocery shelf. There is also nothing quite like harvesting it. A good stand is sort of like a floating prairie – and the sights, sounds, smells and experiences that unfold on rice beds become part of the psyche of the ricer. Hopefully, this is an experience that will still be available to wetland lovers centuries from now.

Related Content

Wetland Coffee Break: Restoring wild rice in Green Bay west shore coastal wetlands

Wisconsin Tribes: Leading the way in protecting and restoring wetlands and watersheds