by Morgan Levey

For one of our recent Wisconsin Wetlands Association staff field trips, we visited our partners (and neighbors) The Wetlands Initiative in Illinois, who walked us through newly constructed wetlands that farmers are putting to work to remove nitrates from field runoff. The following story, adapted from a piece that originally ran in Chicago Magazine, highlights this groundbreaking work that has applications in Wisconsin, too.

On a cold winter’s day, I found myself at a small wetland on the edge of a 30-acre farm outside Princeton, Illinois. A year and a half ago, this 50-foot-wide plot of matted vegetation in shallow water was productive cropland. Now it’s hard at work removing the nitrates put on farm fields from fertilizer application. The Wetlands Initiative built this wetland through a federal conservation program, working with the landowner, who also invested money into the project.

Along with other nonprofits like The Nature Conservancy, The Wetlands Initiative is working with farmers across Illinois to clean runoff by converting small acres at the edges of farm fields to wetlands.

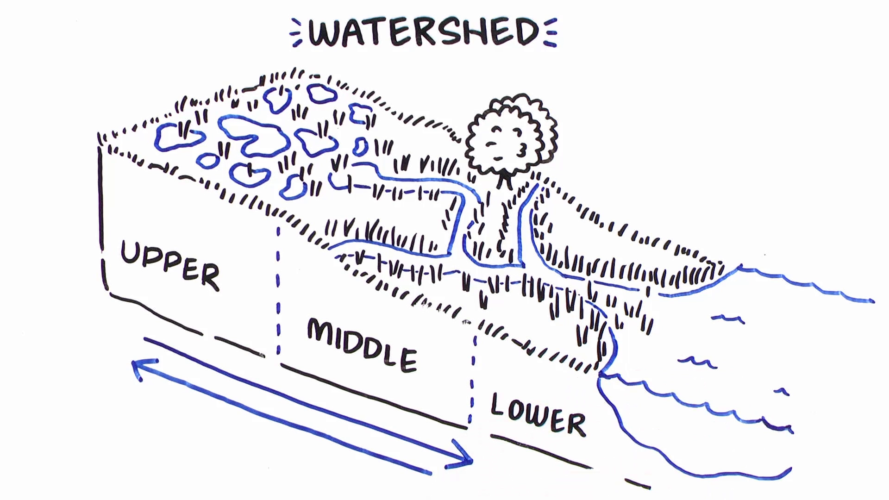

Think of wetlands as Earth’s kidneys, filtering nutrients before they travel to major bodies of water. On average, this particular constructed wetland removes 64 percent of nitrates from the water that flows through it—and it’s only a year and a half old.

When staff from WWA visited the constructed wetlands this summer they were vibrant, full of life, and hard at work cleaning runoff from nearby fields.

Wetlands have long been viewed as wastelands, acres of fertile soil waiting to be drained and farmed. Since the first European settlers, over half of the wetlands in the continental U.S. have been lost. In Illinois it’s closer to 90 percent.

To farm wet land, farmers lay a system of drain tile below cropland to absorb subsurface water—and the associated nitrates—from fields and drain it directly into nearby ditches and waterways.

The nitrates begin as ammonia, the basis for most fertilizers. Ammonia-based fertilizers are often applied in the fall after crop harvest, leaving the fertilizer susceptible to weather and rain. Under these conditions, ammonia easily converts to water-soluble nitrates, and when it rains, the nitrates go wherever the water goes.

An overabundance of nitrates does the same thing in water as it does on land: spurs plant growth. Plant growth in water means algae growth, which blocks sunlight and depletes oxygen levels through its decay process. Algae can grow as a boundaryless mass in the water, creating harmful blooms and hypoxic dead zones, areas where no life can survive. This is happening in a big way in the Gulf of Mexico, and Illinois’ agricultural runoff is a major contributor to the Gulf ’s New Jersey-sized dead zone.

So why not curb the nutrient flow at the source? Edge-of-field constructed wetlands that intercept tile runoff before it enters ditches or streams appear to be a beautiful solution to the nutrient issue. The plentiful microbes found in these shallow wetlands convert harmful nitrates to harmless nitrogen gas. “It’s highly effective, and once these wetlands are in, they’re on pace to work for decades,” says The Nature Conservancy’s Jeff Walk.

And, according to Jill Kostel, environmental engineer for The Wetlands Initiative, constructed wetlands like these are relatively easy to install. The Princeton wetland took about week, but the benefits will be lengthy. “A wetland will just keep working as long as it has water,” she says.

Wetlands aren’t the only combatants against rising nitrate levels, but they might be among the simplest and most enduring.

Read the full story, Can farm wetlands in Illinois stop a dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico?.

Great work using wetlands as solutions to water quality challenges is also happening in Wisconsin. The Nature Conservancy, in partnership with the Fox-Wolf Watershed Alliance, Outagamie County, UW-Green Bay, WDNR, USGS, and others, is constructing wetlands to address agriculture-related water quality issues affecting the Fox and Wolf River watersheds and Green Bay. If you are engaged in other water quality improvement projects that involve wetlands, let us know!

This article originally appeared in our 2018 Volume 3 Newsletter. Want to stay up to date on Wisconsin’s wetlands? Become a member today!

Related Content

Benefits of wetlands

Learn more about the valuable benefits wetlands provide to communities and wildlife.